Sidewalks provide critical infrastructure for pedestrian mobility, and improve public health, traffic safety, and connectivity to public transit and key community destinations.[1] Sidewalks also benefit homeowners: houses located in areas with above-average levels of walkability are associated with a $700 to $3,000 increase in home values.[2]

Yet Tennessee’s largest metro areas average a Walk Score of just 31 out of 100, and in 2023 Tennessee had the 13th highest pedestrian fatality rate.[3] Many Tennessee communities face a sidewalk deficit, with incomplete and poorly maintained sidewalks that lack ADA compliance.[4] Local governments face significant funding challenges in building, expanding, and preserving sidewalks, but examining solutions from cities nationwide can help Tennessee’s local officials to improve walkability.

Key Takeaways

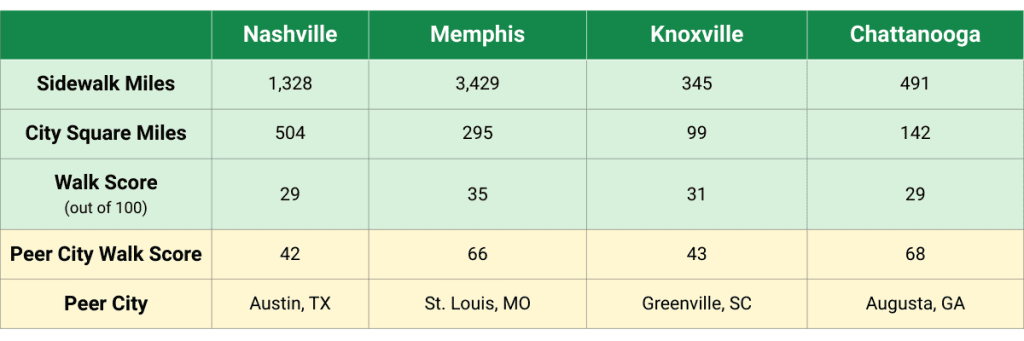

- Tennessee’s largest cities average a 31 out of 100 Walk Score, compared to peer cities’ 51 out of 100.

- Sidewalks are underbuilt due to high project costs, inconsistent funding, and frequent conflicts over who is responsible for construction and maintenance.

- Tennessee cities can consider three strategies from peer cities to improve walkability:

- Updating local sidewalk ordinances with clear policies on exceptions, fees, and responsibilities.

- Adopting alternative revenue sources, such as stormwater fees.

- Developing quick-build programs that offer low-cost walking pathways.

Understanding Tennessee’s Urban Sidewalk Deficit

Sidewalks in Tennessee’s urban areas are defined by two key issues: incomplete or missing sidewalk networks (commonly referred to as a sidewalk “deficit”) or deferred maintenance leading to broken, dangerous, or inaccessible sidewalks.

Tennessee’s largest metro areas average a Walk Score of just 31 out of 100.[5]

Tennessee cities’ low Walk Scores exemplify this sidewalk deficit. Nashville’s pedestrian and biking needs analysis identifies 4,600 miles of “missing sidewalks,” with more than 1,900 miles designated as a significant need — a total greater than the existing sidewalk network. Chattanooga faces similar issues: only 21% of streets have sidewalks, and existing sidewalks are concentrated in the city’s central core neighborhoods.[6] In contrast, Memphis’s sidewalk network of 3,429 miles surpasses all large Tennessee cities combined, but 80% to 95% of the network requires repair or upgrades, exceeding $1 billion in estimated costs.[7]

Sidewalk deficits began with the emergence of the automobile and post-WWII zoning and land-use decisions that pushed urban populations away from dense city centers to sprawling suburbs. Today, Tennessee’s cities face three key barriers in constructing and maintaining sidewalks:

- Sidewalks costs are rising but lack consistent funding – The typical U.S. city spends $30 to $60 per capita annually on sidewalks, but one nationwide analysis suggests completing sidewalk networks requires $80 to $150 per capita annually.[8] Right-of-way acquisition costs have grown significantly due to rising property values – Tennessee’s median home sales price increased for 13 consecutive years, or 112.7% between 2014 and 2024.[9] Yet right-of-way acquisition costs only average an estimated 5 to 10% of total costs, while stormwater infrastructure upgrades for sidewalk construction can double total project costs due to factors such as utility relocation and increasing costs of labor and materials. In total, a sidewalk can cost an estimated $1,000 per linear foot when calculating costs for construction, administrative costs, property acquisition, curbs, stormwater infrastructure and other components.[10] These costs can further escalate due to inconsistent project funding, as project phases (such as surveying or design) start or stop based on available revenue. Unpredictable revenue can prolong project timelines, expose projects costs to inflation, or make prior work obsolete.

- Sidewalks require ongoing collaboration with other departments and agencies – Sidewalk projects often include rerouting underground or at-grade stormwater infrastructure or conflict with existing utilities (such as utility poles). Minor projects therefore quickly escalate and often involve careful, significant planning and collaboration efforts with other agencies and departments such as public water services, gas and broadband companies, and local power providers.

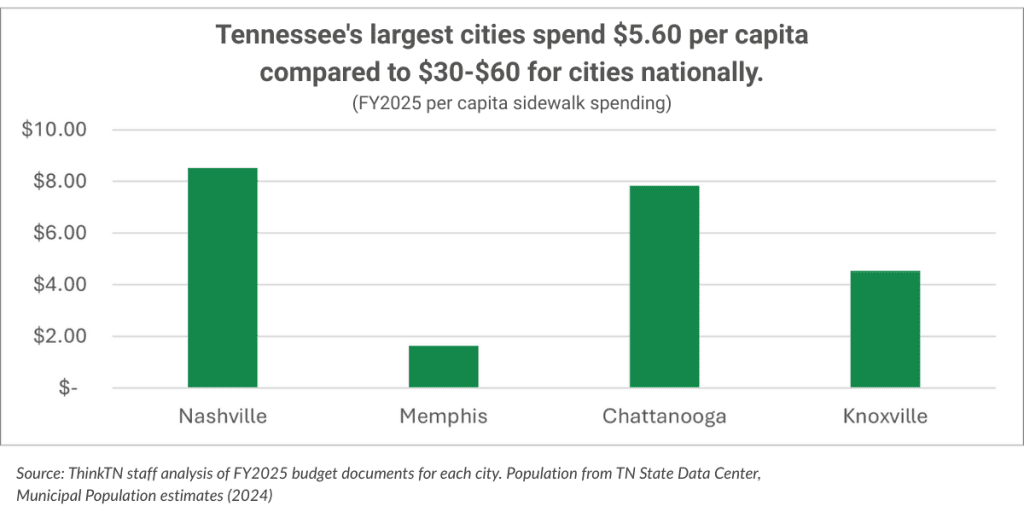

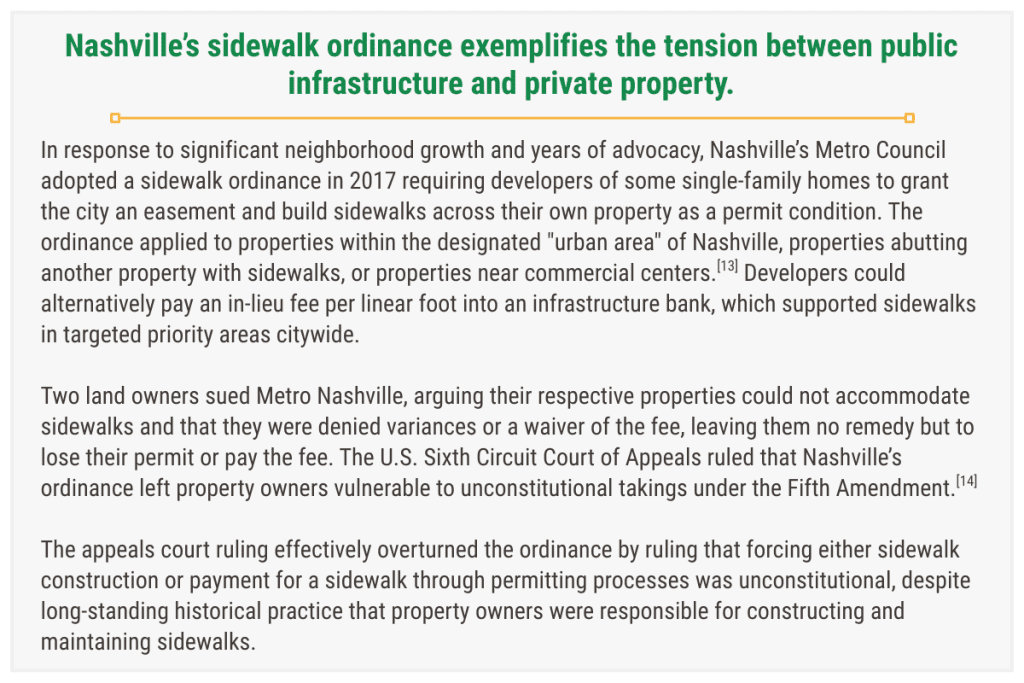

- Cities and properties face confusion and tension over construction & maintenance responsibilities, but shared responsibility is critical to achieving local walkability goals – Tennessee cities have historically assessed adjacent property owners to fund sidewalks. Yet this has frequently resulted in ad hoc repairs and incomplete sidewalk networks, often failing to meet design and accessibility standards, imposing potentially large cost burdens on households, and creating significant enforcement and administrative burdens on cities.[11] Few U.S. cities have chosen to fund the full cost of sidewalk repairs or construction due excessive costs: a survey of 82 cities in 45 states found that 40% require property owners to pay the full cost of repairing sidewalks, 46% share the cost with property owners, and only 13% of cities pay the full cost of repairing sidewalks. [12][13][14] Today, Tennessee cities spend an annual average of $5.60 per capita on sidewalks, compared to a national average of $30 to 60 per capita.

Pathways to Improving Sidewalks in Tennessee

Tennessee cities could consider alternative options to finance, deliver, and maintain sidewalks that would allow for faster and less costly construction and repair of needed sidewalk infrastructure.

-

Consider a local sidewalk ordinance aligned with peer cities that includes clear guidelines for variances, exceptions, and in-lieu fees.

- Houston, TX’s sidewalk ordinance collects in-lieu permitting fees for eligible properties.[15] Developers of new single- and multi-family developments and renovations to any non-single-family residential building are required to build sidewalks or pay a $12 per square foot in-lieu fee. Nine variances are explicitly authorized, including for properties where a sidewalk already exists or was recently constructed, if the sidewalk’s cost exceeds 50% of the total cost of the development, or if a sidewalk would be considered infeasible or unsafe. Neighborhoods are organized into sidewalk service areas, and 70% of revenues are dedicated to districts in which the in-lieu fee was collected. The remaining 30% can be used for sidewalk projects citywide to support equity and safety priorities. Funds are restricted to new sidewalks only and property owners remain responsible for maintaining or repairing existing sidewalks. Similar ordinances also exist in Tampa, Las Vegas, and Austin.

-

Evaluate alternative revenue sources to support city-funded sidewalk projects and ensure sidewalk funding is closely aligned with property owners.

- Ithaca, NY utilizes sidewalk improvement districts to collect and distribute revenue and relieve property owners of sidewalk responsibilities. The city established five sidewalk improvement districts, and the city assesses different fee tiers to allow homeowners of single-family residential properties to pay less than the owners of large commercial and multi-family properties. All revenues are allocated for projects within each respective sidewalk district, supporting public transparency and equally distributed project benefits.[16]

- Denver, CO passed a referendum in November 2022 to shift sidewalk responsibilities to the city. All properties pay a flat fee as part of their stormwater billing based on linear frontage, with an additional scaling fee applied to properties whose street frontage exceeds 230 feet. Raising an estimated $40 million a year, revenues are used for sidewalk construction and repair.[17] Denver also created a process for handling sidewalk encroachments that avoids case-by-case property negotiations, and empowered contractors to expedite repairs with “field fit” protocols rather than sticking to written plans.[18]

-

Develop a program to construct quick-build walking pathways that can be built at lower cost.

- Seattle, WA constructs street-level asphalt or concrete walkways, rather than raised curb or gutter sidewalks. These walkways improve walkability quickly and affordably, with costs averaging one-fourth of the cost of traditional sidewalks.[19] Temporary walkways use flexible, context-appropriate designs (at-grade paths, painted walkways, or simple delineators), helping to prioritize investments, and expand local toolkits, and fill in gaps in existing sidewalk networks.

Outside of an IMPROVE Act referendum (see our blog post on the IMPROVE Act to learn more), Tennessee cities are limited in their ability to raise funds to proactively deliver sidewalks in existing neighborhoods and communities. Looking to successful models in peer cities can help guide Tennessee cities towards more equitable and accessible pedestrian infrastructure.

Special thanks to law clerks Conner Mitchell, Patrick Vandenbergh, Chloe Philpot, and Leezan Kittani for their research contributions to this project.

__________________________________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] Hatem Abou-Senna, Essam Radwan, & Ayman Mohamed. (2022). Investigating the correlation between sidewalks and pedestrian safety. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 166 (March 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106548; see also Poon, L. (2023, February 21). To Build a Healthier City, Begin at the Sidewalk. Bloomberg | City Lab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-21/why-sidewalks-and-street-lights-make-for-healthier-neighborhoods.

[2] Joe Cortright. (2009, August). Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises Home Values in U.S. Cities. American Trails – CEOs for Cities. https://www.americantrails.org/resources/walking-the-walk-how-walkability-raises-home-values-in-u-s-cities.

[3] National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (n.d.). 2023 Ranking of State Pedestrian Fatality Rates. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). https://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/States/StatesPedestrians.aspx AND List of Cities in Tennessee—WalkScore. (n.d.). WalkScore. https://www.walkscore.com/TN/.

[4] See, for example, Nashville’s well documented history of underfunding and underenforcement of sidewalk construction since the invention of the automobile. Rachel Martin. (2017, January 6). Walking in Nashville. Bloomberg | CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-06/why-half-of-nashville-s-roads-still-don-t-have-sidewalks.

[5] Nashville – NDOT WalknBike Plan 2022 (2022, August 26). https://www.nashville.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/NDOT_WalknBikePlan2022_2022.08.26.pdf. Memphis – Memphis Pedestrian and School Safety Action Plan (2015, May). https://bikepedmemphis.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/mpss_action_plan_final_optimized.pdf. Chattanooga – Brianna Williams. (2021, July 15). Breaking down the “Under the Hood” City infrastructure presentation. Nooga Today. https://noogatoday.6amcity.com/breaking-down-the-under-the-hood-city-infrastructure-presentation.). Knoxville – Sidewalk Study. (2020, June). City of Knoxville. https://www.knoxvilletn.gov/government/city_departments_offices/engineering/transportation_engineering_division/sidewalk_study.

[6] Existing Conditions Snapshot—Multimodal Transportation. (2023). Chattanooga – Hamilton County Regional Planning Agency. https://planchattanooga.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ChattAreaPlans_AllTransportationSnapshot_10-26-2023.pdf

[7] See note 5 – Memphis.

[8] Todd Litman. (2023, August 1). Completing Sidewalk Networks: Benefits and Costs. TRB Annual Meeting. https://www.vtpi.org/TRB2024_csn.pdf

[9] Tennessee Home Sales Data (2013-2024). (n.d.). Tennessee Housing Development Agency. https://thda.org/research-and-reports/tennessee-home-sales-data/.

[10] See note 8.

[11] See notes 4 and 8 AND Alexis Corning-Padilla & Gregory Rowangould. (2020). Sustainable and equitable financing for sidewalk maintenance. Cities, 107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102874. AND Michael Pollack. (2024). Sidewalk Government. Michigan Law Review, 122(4). https://doi.org/10.36644/mlr.122.4.sidewalk.

[12] See note 4.

[13] Angie Schmitt. (2017, July 3). Nashville is Finally Tackling Its Sidewalk Problem. Streetsblog USA. https://usa.streetsblog.org/2017/07/03/nashville-is-finally-tackling-its-sidewalk-problem.

[14] Gabriel Tynes. (2023, May 10). Nashville loses battle over sidewalk ordinance at Sixth Circuit. Courthouse News Service. https://www.courthousenews.com/nashville-loses-battle-over-sidewalk-ordinance-at-sixth-circuit/.

[15] See Houston’s original ordinance https://library.municode.com/tx/houston/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1255537 AND Planning & Development—Fee in Lieu of Sidewalk Construction. City of Houston. https://houstontx.gov/planning/sidewalk-fee-in-lieu.html.

[16] Public Works—Sidewalk Policy. City of Ithaca, NY. https://www.cityofithaca.org/219/Sidewalk-Policy.

[17] Department of Transportation & Infrastructure—Denver’s Sidewalk Program. (n.d.). City and County of Denver. https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Department-of-Transportation-and-Infrastructure/Programs-Services/Sidewalks. See also David Zipper. (2025, February 20). Who Should Pay to Fix the Sidewalk. Bloomberg | CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2025-02-20/denver-takes-a-rare-step-to-fund-sidewalks-public-fees-for-repairs.

[18] Jared Brey. (2025, July 31). This City Is Getting Serious About Sidewalks. Will Others Follow Suit? Governing. https://www.governing.com/infrastructure/this-city-is-getting-serious-about-sidewalks-will-others-follow-suit.

[19] Cost Effective Walkways—Fact Sheet. (2019, April). Seattle Department of Transportation – Pedestrian Program.https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SDOT/PedestrianProgram/Sidewalk%20Dev%20Program/CostEffective_Walkway_FactSheet_v4.pdf.